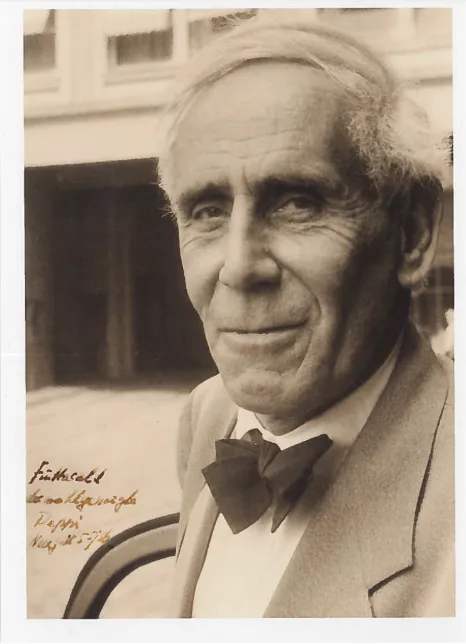

Emil Julius Gumbel (1891 - 1966)

Born in Munich in 1891 into a wealthy liberal Jewish family, Gumbel spent a typical childhood in Munich's open-minded Lehel district. After his school years at St. Anna and Wilhelmsgymnasium, he studied mathematics and economics at LMU and was awarded a doctorate in political science (Dr.oec.publ.) in 1914. Like many of his peers, Gumbel was initially a war volunteer, but was transformed into a “militant pacifist” within a few months as a result of the terrible experiences, the death of his brother and cousin and the influence of his uncle Abraham, who had made a name for himself in anti-militarist circles. As an early member of correspondingly journalistic associations such as the “Bund Neues Vaterland”, he made friends with prominent like-minded people during the war, including Carl von Ossietzky, Albert Einstein and Kurt Tucholsky. These connections were often to last a lifetime. However, his commitment to pacifist and socialist goals was life-threatening in the uncertain years of the early Weimar Republic, and it was only by chance that he escaped being shot by soldiers of a rifle division in 1919.

His book “Zwei Jahre Mord” (Two Years of Murder), his investigation into the legal aftermath of politically motivated murders published in 1921, had the effect of a drumbeat. Using meticulously researched evidence, he was able to prove that the capital crimes committed by the right-wing camp not only far outnumbered those committed by opponents, but were also downplayed in legal terms and punished almost laughably leniently. Official investigations could not shake the validity of his work; the statistician Gumbel had worked too precisely and methodically unimpeachable for that - a principle that he maintained during the following years, in which he also gained an international reputation as an unwavering advocate of democracy and as an early chronicler of right-wing terror and secret rearmament. He also emerged as a translator of the British mathematician and pacifist Bertrand Russell and prepared an (unpublished) edition of Karl Marx's “Mathematical Manuscripts”.

He had single-mindedly pursued his scientific career over the years. After further studies in Berlin, Gumbel became a private lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, where he qualified as a professor in 1923. However, his political commitment contradicted the conventions of the prevailing academic milieu. From 1924 onwards, opposing colleagues and right-wing fraternities attempted to end his university career in several disciplinary proceedings. He became persona non grata at the university, his family was harassed and the national press organized a hooliganism against him. After the beginning of the Nazi regime, his writings were banned and burned. He was the first academic of the Weimar era to lose his position at the university - due to his political ideals and convictions - before the beginning of Nazi rule in the summer of 1932.

The first “expatriation list”, which included the mathematician Gumbel alongside politicians and publicists who are still prominent today (such as Rudolf Breitscheid, Kurt Tucholsky, Alfred Kerr, Lion Feuchtwanger, Heinrich Mann, Willi Münzenberg and Philipp Scheidemann), was hailed in Nazi jargon as an instrument for eradicating “traitors to the people from the German body politic”. From 1933 onwards, Gumbel was able to build a new life, including an academic one, in exile in France. After the invasion of German troops in 1940, he was forced to make a spectacular escape to New York via Spain and Portugal. His family only reached him in 1941 by a circuitous route, but at least they were unharmed. Despite reprisals in the McCarthy era, in which the mere suspicion of communist interests and relationships with communists could ruin entire careers, Gumbel also managed to establish himself as an excellent mathematician in New York. He was now able to build on the foundations of extreme value statistics that he had developed during his time in Lyon and become a globally respected specialist in this field.

His scientific legacy, the book “Statistics of Extremes” (1958) is still standard today, every statistician knows the Gumbel distribution and the Gumbel copula and no hydraulic engineering project (such as dams or dykes) is realized without his formulas, which have also become common tools in many other areas (e.g. the calculations of breaking strengths of materials, lifetime distributions in insurance, financial losses in banking).

Gumbel's political achievements, on the other hand, were largely forgotten - it was only in the 1960s that the well-known lawyer, writer and children's book author Heinrich Hannover, still in personal contact with Gumbel, addressed his work in the context of legal-historical studies on the Weimar Republic. Until the 1990s, when a few studies on Gumbel were published, followed by sporadic further studies up to the present day, he remained a voice crying in the wilderness, even though (or precisely because?) Gumbel and his achievements in both areas were never controversially discussed, but were always unanimously praised for the exemplary qualities of his professionalism and courage.

When Gumbel died in 1966, the transatlantic professional world mourned the loss of an excellent colleague. In Germany, on the other hand, he was almost forgotten, a man of whom one could have been proud because he had remained upright when others were writhing under the Nazi ideology.

Emil J. Gumbel (1891 - 1966)

Statistician, pacifist, publicist. In the fight against extremes and for the Weimar Republic

Past dates:

Exhibition March 24, 2025 - Mai, 14 2025, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

main building, Unter den Linden 6, as part of the DAGStat 2025 conference (www.dagstat2025.de)

Vernissage January 10, 2025 - February 7, 2025: University of Konstanz & VHS Landkreis Konstanz

vhs main office Constance, Katzgasse 7, 78462 Constance

Exhibition May 5, 2024 - July 31, 2024: University of Hamburg

Geomatikum, University of Hamburg, Bundesstraße 55, 20146 Hamburg

Exhibition November 21, 2023 - March 28, 2024: Helmut Schmidt University, Hamburg

Holstenhofweg 85, 22043 Hamburg

Exhibition November 18, 2019 - January 31, 2020: Foyer of the MATHEMATIKON

Im Neuenheimer Feld 205, 69120 Heidelberg

Exhibition July 15, 2019 - October 19, 2019: Heidelberg University Museum

Grabengasse 1, 69117 Heidelberg

Exhibition April 26, 2019 - May 31, 2019: Technical University of Munich

Arcisstraße 21, 80333 Munich